The Legacy of Stan Cox: One man’s mission to keep Black history in Indiana alive

The Legacy of Stan Cox

A vibrant Black church in South Bend. A nearly forgotten one in Lebanon. A historic lake resort in Angola. A neighborhood built by Black war veterans in Indianapolis.

Each of these places, scattered across Indiana, tells a story that could have easily been erased. Once threatened by time, neglect, or bulldozer, they now endure. While many people have fought to preserve them, one man deserves special attention: Standiford “Stan” Cox.

Born into the Jim Crow-era in rural Indiana, Cox rose to become the first Black chemist at Eli Lilly and Co. But his most remarkable legacy lives beyond the lab. Through two philanthropic funds he established at Central Indiana Community Foundation (CICF), Cox has become one of Indiana’s most influential figures in Black historic preservation.

Over the past five years, Cox’s funds have contributed more than $1 million to preserving Black historic sites in Indiana. As the years pass, his legacy will continue to ensure that the places and stories of Black communities across the state will never be forgotten.

From Brazil to Breakthrough

Stan Cox was born in 1934 in Brazil, Indiana, one of five children raised by Chester and Dovie Stewart Cox. His grandfather had moved the family from Chesterfield County, Virginia, to work in the coal mines of Clay County. The elder Cox eventually rose to become superintendent of the mines, a remarkable achievement for a Black man in that era.

Stan’s father, Chester, still a boy when he arrived in Brazil, later worked briefly in the mines himself before finding more stable work in maintenance at the local Chevrolet dealership. Dovie, Stan’s mother, had grown up in Lost Creek Settlement, a historic community in Vigo County founded by free people of color in the early 1800s.

Raising a Black family during the Great Depression in a segregated town required resilience. Carl Cox, Stan’s younger brother by four years, recalls their father’s words: “You’re concerned about segregation, but these old-timers will die off, and the future is going to be brighter.”

Chester was especially inspired by the story of pioneering Black chemist Percy Lavon Julian, who had earned his degree just up the road at DePauw University. That admiration shaped his parenting. “He’d say, ‘Don’t give up. Make them decide they won’t let you succeed because of your race—not because you can’t do the job,’” Carl recalls.

The message stuck. Four of the five Cox children went to college. Stan graduated valedictorian from Brazil High School, earned degrees from Indiana University and Butler University, and was inducted into the prestigious honor society, Phi Beta Kappa. In 1957, he broke the color barrier at Eli Lilly, becoming the company’s first Black chemist.

But Stan wasn’t one to boast about his achievements. “He wasn’t that type of person,” Carl says. “That would be bragging.” Instead, Stan was focused and persistent. “He was very direct and concentrated. He’d set a goal and quietly work toward it.”

Preserving the Places That Shaped Him

Stan Cox rarely spoke publicly about his philanthropy. But those closest to him believe it was deeply personal. Carl Cox traces Stan’s commitment back to weekends at Lost Creek Settlement, visiting their mother’s side of the family. Even as his professional success brought him financial wealth, Stan never forgot the communities that helped raise him.

One of his first major gifts was establishing the Dovie Stewart Cox & Chester A. Cox Sr. Memorial Fund at CICF, dedicated to supporting the maintenance of the Lost Creek Community Grove, a vital gathering space for the descendants of the settlement.

“He figured if other people could give to causes they care about, why couldn’t he give to the ones that mattered to him?” Carl says.

But Stan didn’t stop there. Working with CICF, he launched the Standiford H. Cox Fund to support the preservation of African American historic sites across Indiana. Leah Nahmias, a program director at CICF, says the fund’s laser focus on Black preservation makes it exceptionally rare. “There just aren’t many donor-driven funds that support a specific cause at this scale.”

Together, the two funds distribute upwards of $230,000 annually. While CICF manages the fund, the heritage preservation nonprofit Indiana Landmarks plays a leading role in identifying grantees. According to Nahmias, the partnership is both unique and critically important.“Indiana Landmarks not only brings expertise around historic preservation to the table, but they have a full-time program focused on black historic preservation, which is really unique in the country.”

The Black Heritage Preservation Program at Indiana Landmarks, led by veteran journalist and historian Eunice Trotter, was launched in 2023 to strengthen this very work. It distributes $200,000 per year to similar efforts across the state.

“That we have someone dedicated full-time to preserving Black history at the state level is incredibly rare,” Nahmias adds. “To also have a donor like Stan making such a huge impact, it’s extraordinary.”

In just five years, the Cox Fund has supported more than 70 preservation projects. While the structures themselves are significant, the stories they tell are beyond value.

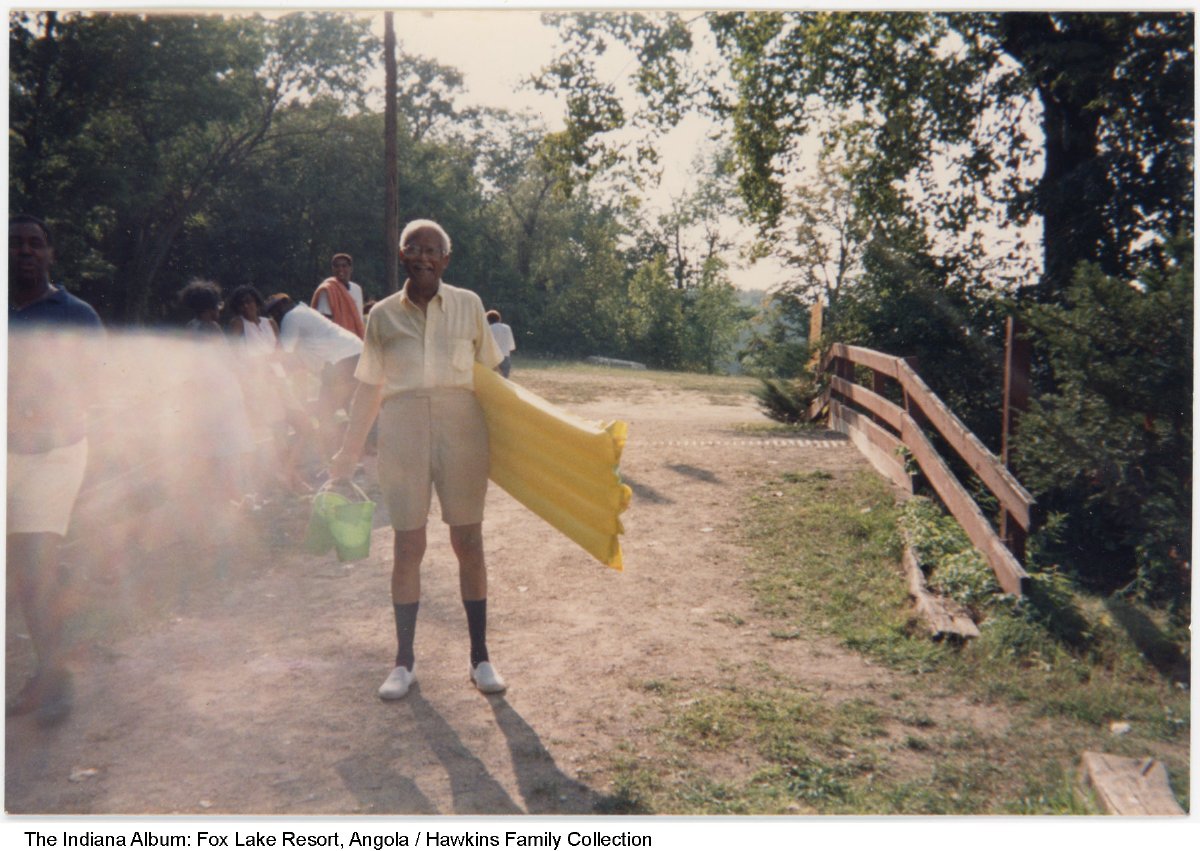

Fox Lake: A Refuge Remembered

In the 1920s when Fox Lake Resort was platted, it was the only lake among more than 100 in Steuben County where Black residents were allowed to buy property. Kathryn Hawkins, an Indianapolis lawyer, knows its story well. Her paternal grandparents honeymooned there in the 1940s. Hawkins herself was “dipped into the lake” at three months old. “Back then, being Black and finding a place to vacation—not just in Indiana, but the United States—wasn’t easy,” she says.

Fox Lake welcomed Hawkins’ family, offering respite not just from summer heat but also from the indignities of Jim Crow-era discrimination. Her grandparents eventually purchased a cottage there, which remains in the family today.

In 2001, the resort community was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Though still predominantly Black today, the resort has become racially diverse. But according to Hawkins, one thing hasn’t changed. “It has always been a refuge from everyday life. When I’m there, I still feel that.”

Understanding its significance not only to her family but to so many others, Hawkins helped establish the Fox Lake Preservation Foundation to protect the community’s historic character. A $15,000 grant from the Standiford H. Cox Fund recently supported repairs on the K.T. Thompson Lodge, including a new roof and structural reinforcements—work essential to maintaining the structure’s integrity.

But Hawkins says it’s about more than rehabilitation. “Its history is important, and telling its story accurately is also incredibly important,” she says. Reflecting on the generosity of Stan Cox, she adds, “The world needs more people like him. Just unconditionally generous, and who recognizes the true value of preserving our past.”

Lebanon AME Church: Lifting a Forgotten History

The small town of Lebanon, Indiana, isn’t often associated with Black culture. Today, fewer than 1 percent of its residents are Black. But a small, thriving community of African Americans once called it home. Missy Krulik, the city’s Main Street director, discovered that history when a friend showed her an abandoned African Methodist Episcopal Church, built in 1880.

“There was barely anything in the local archives about the church,” Krulik says. “It was like this community had been forgotten.”

Determined to preserve not only the building but the stories it contained, Krulik approached her husband with an ambitious proposal: they would restore the church themselves. “We dove in headfirst,” she recalls. Contractors initially expressed doubts about the project’s feasibility. “A lot of them actually said, ‘Why don’t you just tear this down, it’s in such bad shape?’ But it’s about preserving the history, because once a building is gone, it’s gone.”

A $30,000 grant from the Cox Fund proved crucial, allowing them to lift the building, install a new foundation, and begin preserving the church’s historical features.

“This church had maybe 20 parishioners at its peak,” Krulik says. “But they were barbers, farmers, and civic-minded people. One of them, James King, was so involved in local politics he had a street named after him. They mattered.”

When finished, the restored church will serve as a living museum highlighting the forgotten history of Lebanon’s Black community. “The Black heritage within the Lebanon community hasn’t ever really been showcased,” Krulik says. “This will be one small way to change that.”

Flanner House Homes: A Neighborhood Worth Noticing

Just west of downtown Indianapolis, the Flanner House Homes Historic District stands as a testament to resilience and self-determination. Built in the 1950s through a cooperative project led by community leader Cleo Blackburn, the neighborhood enabled Black World War II veterans facing discriminatory housing policies to build their own homes.

Disa Watson lives in a home her father built. She has become a vocal defender of the neighborhood’s legacy, pushing back against unfounded myths. “There is a misconception that everyone who built this neighborhood was poor, and that is far from the truth,” Watson emphasizes. “Just because it was a ‘Black area’ does not translate into ‘poor.’ We had teachers, firefighters, and business owners who were part of this project.”

Watson also defends the neighborhood against existential threats. In 2013, she helped halt a plan to demolish several homes to build a big-box store. More recently, she sought funding for signage that clearly identifies the neighborhood’s rich historical significance once and for all. The Cox Fund supported the effort, resulting in a bright green sign at the neighborhood’s entrance, complete with a gold key symbolizing homeownership.

“We want people to know they are coming through an important neighborhood,” Watson says. “Slow down. Recognize where you are.” The sign, Watson says, “represents the fact that this project impacted 180 families, and that is really a key foundation to the American Dream.”

As for Stan Cox, she says, “It means so much that his legacy helped us achieve this goal. It’s an honor for Historic Flanner House Homes to be part of it.”

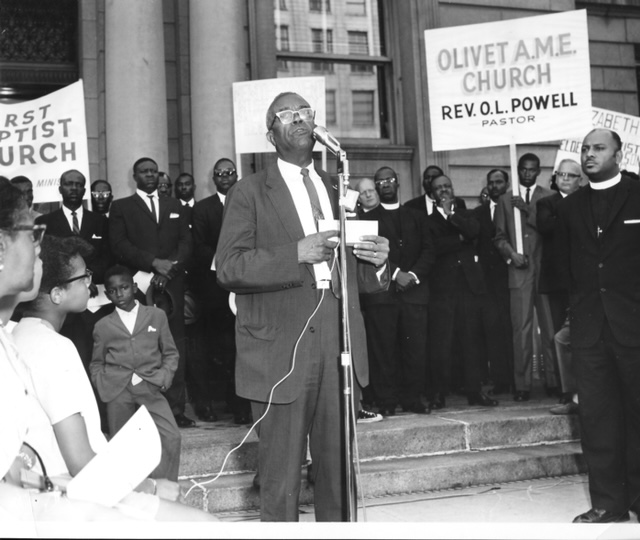

Olivet AME Church: The Soul of South Bend

Founded in 1870, Olivet AME Church was the first African American church in South Bend, established just five years after the city itself. For more than 150 years, the church has been a cornerstone of Black history, hosting abolitionist Sojourner Truth, advocating for civil rights, and organizing community initiatives.

Alma Powell, a lifelong congregant and current chief steward, has seen Olivet’s pivotal role firsthand. Yet, despite its vibrant legacy, the church’s aging building faced significant issues: mold infiltrated the Sunday school classrooms, and the front stairs were deteriorating and inaccessible for those with mobility challenges.

Thanks to a $15,000 grant from the Cox Fund, vital repairs—including new front steps and mold remediation—are underway. Powell emphasizes the importance of the updates: “We have beautiful stained glass, a pipe organ, a sanctuary that just stuns you when you walk in. But this is an old building, it takes a lot to maintain. Without the Cox Fund, we couldn’t have done it.”

While many of the repairs supported by the Cox Fund are structural, their impact on the lives of congregants are enormous. For example, updates to the crumbling front stairs will finally bring the church into ADA compliance. For years, churchgoers in wheelchairs or with other challenges were forced to access the building through the back door. Thanks to the Cox Fund, they’ll now be able to enter through the front.

Powell isn’t simply grateful for Stan Cox. She feels a personal connection to him. Like him, she attended Indiana University during a time of limited opportunities for Black students. She knows what it was like to have lived through a period of American history when Black culture was regarded as disposable. “He probably saw heritage being erased, or hidden. That’s why this work is so important.”

The Weight of One Life

Stan Cox spent a lifetime deflecting attention, achieving historic firsts with little interest in public accolades. Given his reserved personality, his story might easily have remained untold, lost to the shadows of history.

Yet his extraordinary philanthropic legacy stands as a monument to his memory. And every year—with every roof restored, every narrative unearthed, every community reconnected to its roots—that legacy grows stronger.

Mark Dollase has witnessed Stan’s philanthropic impact firsthand. As vice president of preservation services at Indiana Landmarks, he helps evaluate and select Cox Fund grantees. Dollase doesn’t shy away from lofty language when discussing Stan’s contribution to Black heritage in Indiana. “To use a religious term, it’s manna from heaven,” Dollase says. “He’s funding projects that oftentimes have a very difficult time getting access to funding.”

Eunice Trotter, director of Indiana Landmarks’ Black Heritage Preservation Program, echoes that sentiment. “Sites are evidence of the stories. Stan Cox ensures these stories are never lost.” She emphasizes, “Think about this: One man, Stan Cox, is doing as much to preserve Black history as our statewide preservation program. His impact will be felt for generations.”

For Carl Cox, Stan’s brother, it’s the deeply personal side of Stan’s generosity that resonates most profoundly. Carl often thinks of the Community Grove at Lost Creek, and how Stan intervened to save that simple yet sacred place. “He was able to help make sure they continue to have a place to play tennis, horseshoes, and baseball on the weekends,” Carl says.

When Stan broke the color line at Eli Lilly, Carl recalls their community jokingly cautioning Stan: “Don’t embarrass us.” Carl laughs warmly at the memory. “I guess he did alright.”

Today, Stan’s quiet determination resonates deeply across communities throughout Indiana. Alma Powell still finds herself reflecting on Stan’s journey, wondering about the inner spark that drove him so profoundly. “What was it about growing up in Brazil, Indiana, as a Black man, that gave him this deep desire to preserve?” Powell asks. “I think I know the answer. But I’d love to hear it from him.”

In a world driven by fleeting headlines and images, Stan Cox has built something truly indelible. As a chemist, he understood what it meant to preserve essential elements, to protect something vital from disappearing. Yet the legacy he crafted isn’t about mixing elements to form something new—it’s about carefully safeguarding the fundamental essence of Black heritage, ensuring that its stories, places, and truths remain intact.

Brick by brick, place by place, Stan Cox is making sure that Indiana’s Black history—so long overlooked—will be remembered for generations to come.